Now Reading: Justices Consider Congressional Speeches as Legal Trials

-

01

Justices Consider Congressional Speeches as Legal Trials

Justices Consider Congressional Speeches as Legal Trials

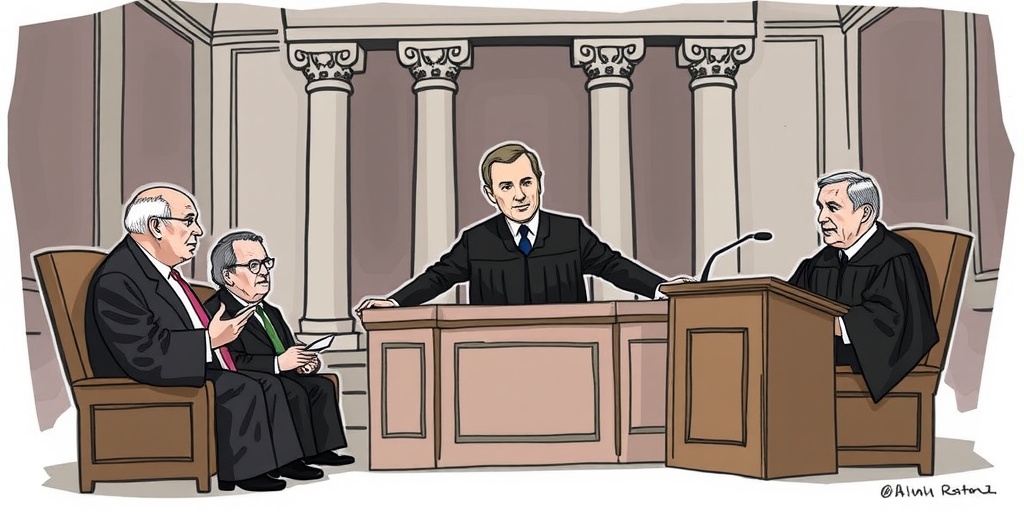

Supreme Court Justices Reflect on the State of the Union Address Tradition

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. maintains a regular presence at the State of the Union address, a tradition he openly regards with discomfort. In the past, he has described it as “a political pep rally,” and his attendance seems more a product of obligation than enjoyment. This year’s address saw him accompanied by Justices Brett M. Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, both appointed by President Trump, along with Justice Elena Kagan, appointed by President Barack Obama, and retired Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, a selection of President Reagan.

Roberts, who was appointed by President George W. Bush, articulated his ambivalence towards the event back in 2010, noting the troubling image presented by justices sitting expressionlessly while members of Congress engage in animated reactions. He questioned the appropriateness of having members from one branch of government crowding around the Supreme Court while the justices remain stoic. Despite his reservations, Roberts has continued to attend, while other justices have long since opted out. Notably, Justice Clarence Thomas has not participated in the address for over a decade, citing discomfort with the “catcalls, the whooping and hollering and under-the-breath comments” that often accompany the speeches.

Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. shared similar sentiments, calling the State of the Union addresses “very political events” and “very awkward.” Alito has only attended once since 2010, during which he found himself in the precarious position of silently responding to President Obama’s critique of the Supreme Court’s ruling on the Citizens United case. In that instance, he was compelled to mouth the words “not true” before retreating from future appearances.

Scholars have observed that the likelihood of Supreme Court justices attending the State of the Union address diminishes with their age and length of service on the bench. Early attendance may stem from feelings of loyalty and gratitude to the president who appointed them. As the late Justice Antonin Scalia once remarked, it is easier to remain engaged when “the president giving the State of the Union is not the man who appointed you.”

The stress associated with attendance at such events is evident through the justices’ remarks. Their participation often involves making careful decisions about which statements from the president constitute safe grounds for applause. Justice Alito pointed out the challenge of this task, particularly because presidents may lead off with innocuous statements that later shift toward more contentious topics. He recounted instances where one might start to applaud, only to be faced with politically sensitive remarks, saying, “Isn’t this the greatest country in the world?” might quickly turn into, “Because we are conducting a surge in Iraq,” prompting them to stop clapping abruptly.

In stark contrast to today’s more cautious approach, historical precedents show a time when Supreme Court justices were more openly engaged. For instance, in 1964, during President Lyndon B. Johnson’s address, Chief Justice Earl Warren and four other justices applauded when Johnson proclaimed that the current Congressional session had achieved more for civil rights than any in the last century.

Reflecting on the current climate during a 2019 interview, Chief Justice Roberts noted the necessity for justices to limit their applause and engagement significantly. “It’s not our job to express support for particular policy initiatives,” he stated. Consequently, the justices often remain silent, sitting “like mannequins” throughout the address, an observation he humorously extended to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who find themselves in a similar position of restrained decorum.

As the tradition of the State of the Union address continues, the Supreme Court justices face a complex interplay of institutional protocol and personal comfort. Their attendance—or lack thereof—serves as a fascinating reflection of the evolving relationship between the judiciary and the legislative branches of government and raises questions about the role of justices in the broader political landscape. With each passing year, this tension becomes more palpable, as justices navigate the fine line between being impartial arbiters of justice and participating in a highly charged political event.

Stay Informed With the Latest & Most Important News

Previous Post

Next Post

-

01New technology breakthrough has everyone talking right now

01New technology breakthrough has everyone talking right now -

02Unbelievable life hack everyone needs to try today

02Unbelievable life hack everyone needs to try today -

03Fascinating discovery found buried deep beneath the ocean

03Fascinating discovery found buried deep beneath the ocean -

04Man invents genius device that solves everyday problems

04Man invents genius device that solves everyday problems -

05Shocking discovery that changes what we know forever

05Shocking discovery that changes what we know forever -

06Internet goes wild over celebrity’s unexpected fashion choice

06Internet goes wild over celebrity’s unexpected fashion choice -

07Rare animal sighting stuns scientists and wildlife lovers

07Rare animal sighting stuns scientists and wildlife lovers